Table of Contents

You didn’t ask to be here. One minute you’re driving down I-25, listening to a podcast, thinking about dinner. The next, you’re watching a Ram 2500 plow into a Subaru Outback, all twisted metal and shattered glass. You did the right thing—you pulled over. You talked to the police. Now, someone’s lawyer is asking for a written statement.

And you think, “Sure, I’ll help.” You jot down a few sentences: The truck seemed to be going too fast and hit the car. You send it off, feeling good.

Except you just handed the truck driver’s insurance company a gift.

Because “seemed to be going too fast” is a guess. An opinion. And insurance companies—those soulless, spreadsheet-driven behemoths—don’t just like guesses. They feast on them. They use your vague, well-intentioned words to deny claims, delay justice, and leave injured people holding the bag.

They’re counting on you to be sloppy. We’re not going to let that happen. Learning how to write a statement as a witness isn’t about being a good writer—it’s about building a fortress of fact that no adjuster can tear down.

This Is How You Dismantle an Insurance Adjuster’s Game

Your witness statement isn’t just a piece of paper. It’s a weapon. When written correctly, it becomes a clean, sharp, undeniable record of the truth—a truth that insurance companies are paid to obscure.

They thrive on chaos. On confusion. On your natural uncertainty about what you saw. Their entire business model is built on manufacturing doubt.

Your job is to give them none. Zero. You will write a statement so precise, so chronological, so utterly grounded in fact that the adjuster’s usual playbook becomes useless. They want ambiguity? You’ll give them a blueprint. They want opinions? You’ll give them physics.

This isn’t about flair. It’s about fire. It’s about protecting an innocent person from a corporation that sees them as a line item on a balance sheet. As a lawyer who has recovered over $50 million for Colorado injury victims, I’ve seen garbage statements sink slam-dunk cases. And I’ve seen sharp, detailed accounts force stingy insurers to pay what they owe.

Your words have that power. Let’s learn how to use them.

The Anatomy of a Bulletproof Witness Statement

Forget what you’ve seen on TV. A powerful witness statement isn’t a rambling monologue. It’s a surgical instrument—clean, structured, and brutally efficient.

We’re building a wall here, brick by factual brick. Insurance adjusters are professional demolition experts, paid to find the tiniest crack in your story. So we will give them no cracks.

Step 1: The Unskippable Opening Salvo

Every statement begins with the basics. No exceptions. This isn’t creative writing—it’s a declaration.

It must include:

- Your Full Legal Name: No nicknames, no shortcuts.

- Your Current Address and Phone Number: They need to be able to find you.

- The Declaration of Truth: A single, powerful sentence. "This statement is true to the best of my knowledge and recollection."

This isn’t just busywork. It’s your first layer of armor. Leaving it out is a rookie mistake adjusters celebrate.

Step 2: Build the Timeline, Brick by Brick

The body of your statement tells the story. And that story must move in one direction: forward. Chronological order is non-negotiable.

Use numbered paragraphs. It’s not just for looks—it forces you into a logical sequence and makes your account impossible to misinterpret.

Your first paragraph must set the stage with military precision.

Example:

1. On July 15, 2024, at approximately 2:30 PM, I was stopped at a red light in my vehicle. I was in the westbound lane of Colfax Avenue at its intersection with Speer Boulevard in Denver, Colorado. The weather was clear, the sun was out, and the road surface was dry.

Every paragraph after that is the next beat in the story. What happened first? Then what? Then what? This simple structure slams the door on the adjuster’s favorite game: twisting your timeline into a pretzel.

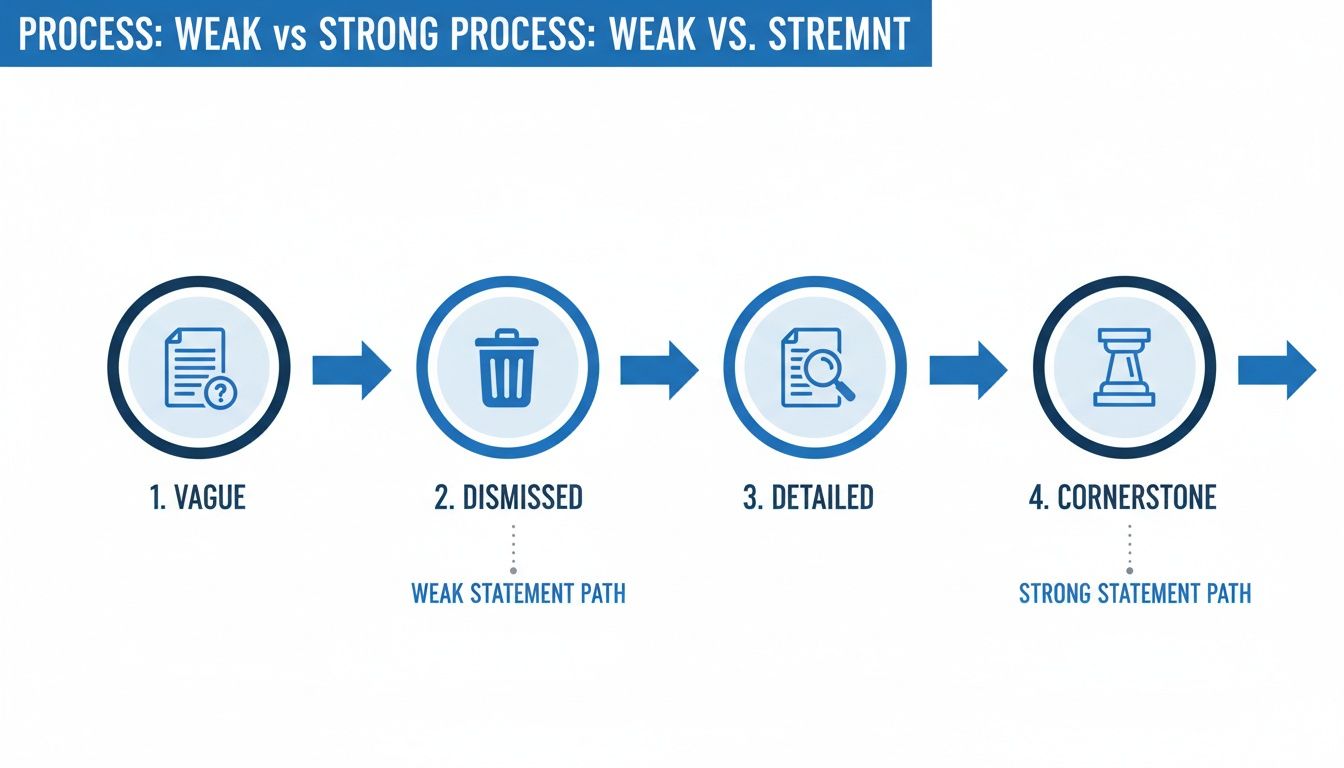

A vague, disorganized story is a gift to the other side. A detailed, chronological one is a cornerstone—the foundation for a just outcome.

Step 3: The Sacred Line Between Fact and Opinion

This is it. The single most important rule you will follow.

State what you observed, not what you concluded.

Insurance companies will take any opinion, any guess, any assumption you make and use it as a sledgehammer to shatter your credibility. Don’t give them the weapon.

- This is a FACT: "I saw the red Ford F-150 enter the intersection while the traffic light for its lane was red."

- This is an OPINION: "The driver of the red truck was being reckless and wasn't paying attention."

Stick to what your senses told you—what you saw, what you heard, what you smelled. Did you hear a horn? Say so. Did you see a driver’s head down, illuminated by the glow of a phone? Write that down. Those are sensory facts. They paint a picture without straying into the deadly territory of speculation.

You aren’t just writing a letter. You are creating a piece of evidence. Your statement has to hold up, even if there isn't an official police report. If you need to understand that process, you can learn more about how to make an insurance claim without a police report.

The Dirty Trick Insurance Companies Don’t Want You to Know

Insurance companies have a thick, cynical, ruthlessly effective playbook. And their favorite play—the one they run again and again—is to find one tiny inconsistency in your story and use it to burn your entire testimony to the ground.

The trick insurance companies don't want you to know is that they treat your honest estimates as lies.

They aren't looking for the truth. They are hunting for contradictions.

Let's say you see a car run a red light. At the scene, you tell the cop, "Yeah, the guy was flying—maybe 50 mph." Later, in your written statement, you write, "The car was traveling at a high rate of speed, approximately 45-50 mph."

To you, that’s the same thing. An honest guess.

To the insurance adjuster? It's a "gotcha" moment. They will argue, with a straight face, that you are an unreliable witness who can’t keep their story straight. It’s a dishonest, cynical tactic. And it works.

Shut It Down: Certainty vs. Observation

You beat them at their own game by being relentlessly precise. You draw a bright, uncrossable line between what you know for a fact and what you merely observed. You write defensively.

- When you are uncertain: Use cautious, observational language. "The car appeared to be traveling faster than other traffic." This isn't weakness; it’s unshakeable credibility. You're acknowledging you don't have a radar gun.

- When you are certain: State the fact directly. "The traffic light for the northbound lane was red." No wiggle room. No interpretation.

Here’s how you translate vague thoughts into bulletproof facts:

| Instead of This (Speculation) | Write This (Observation/Fact) | Why It Obliterates Their Argument |

|---|---|---|

| "He was going about 50 mph." | "The car appeared to be traveling faster than other traffic." | It's a defensible observation, not a failed attempt at being a radar gun. |

| "The driver looked drunk." | "The driver was swerving between lanes and I smelled alcohol on his breath after the crash." | Sticks to specific, observable actions and sensory details—not a medical diagnosis you aren't qualified to make. |

| "She wasn't paying attention." | "I saw the driver looking down at a glowing screen in her lap for at least three seconds before the impact." | Replaces a guess about her mental state with a specific, factual action you witnessed. |

They want to create confusion. You are going to give them crushing clarity.

Their whole business often relies on these bad faith tactics. If you want to see just how deep the rabbit hole goes, you can learn more about finding an insurance bad faith lawyer in Colorado and see how these fights are won.

Writing With Clout: Turning Vague Into Victorious

We’ve dodged the traps. Now it’s time to go on offense. This is where your statement transforms from a simple account into a powerful piece of evidence that can win a case.

The secret is specificity. Vague statements die on an adjuster’s desk.

“The car was going fast” is useless. But “The engine roared, and the sedan passed me so quickly my car shook”? That’s a sensory fact. It puts the reader in the passenger seat. That’s how you write with clout.

Paint a Picture With Facts, Not Flair

This isn’t about becoming a poet—it’s about being a high-definition camera. You need effective written communication skills to translate what you saw/heard/smelled into undeniable text.

- Sight: Not “a green car.” It’s “a dark green, four-door Honda Civic with a busted right taillight.”

- Sound: Not “a crash.” It’s “the high-pitched screech of tires for two full seconds, followed by the crunch of metal and shattering glass.”

- Admissions: Did you hear the at-fault driver say something? This is pure gold. “He got out of his truck and immediately said, ‘I’m so sorry, I was looking at my phone and never saw him!’” That’s a direct admission of fault. That’s a case-winner.

Weave In Your Proof

If you took photos or videos at the scene—and you always should, if it’s safe—they become exhibits. You must formally tie them to your written account.

Label your evidence and point to it directly in your narrative.

Example:

4. Immediately after the collision, I saw the driver of the red truck throw a beer can into the bushes. See Exhibit A, a photo I took at 3:10 PM showing the Coors Light can next to the truck's front tire.

You’re creating a closed loop of logic. An assertion backed by immediate, documented proof. It’s devastatingly effective.

Quantify Everything

Numbers are the enemy of ambiguity. Insurance adjusters live in the grey areas—your job is to eliminate them.

| Vague and Weak | Specific and Strong |

|---|---|

| "He was tailgating for a while." | "He was driving less than one car length behind the SUV for at least three city blocks." |

| "The light was red for a bit." | "The traffic light in his direction had been red for at least five seconds before he entered the intersection." |

| "He was on the phone." | "I saw him holding a black phone to his left ear from the moment I first noticed his car until the impact." |

This isn’t just good practice. It’s how you turn your words into leverage.

The Final Polish: Sign, Seal, and Protect Your Statement

You’ve done the hard work. You’ve built your fortress of fact. But don’t stumble at the finish line.

These final steps are non-negotiable. This is where you lock the doors and set the alarm.

Proofread Like a Lawyer

Read your statement out loud. Slowly. For every single sentence, ask: "Is this 100% accurate and something I personally observed?"

This is your last chance to hunt down and kill any lurking opinions. "He was speeding" becomes "His car was traveling much faster than the flow of traffic." Seal your credibility in concrete.

The Statement of Truth

At the end of your document, right above your signature line, you must add a formal declaration. This transforms your story into sworn testimony.

In Colorado, the language is specific. Use this exact phrase:

"I declare under penalty of perjury under the laws of the State of Colorado that the foregoing is true and correct."

That sentence carries the weight of the law. Use it.

Sign, Date, and Keep It Safe

You must sign and date your statement. An unsigned document is worthless. Consider getting it notarized—it adds another layer of authentication that makes it harder for an adjuster to challenge.

Now for the most important rule of all.

Never, ever give your statement directly to the at-fault party's insurance adjuster.

I will repeat that. Never, ever give your statement directly to the at-fault party's insurance adjuster. Their only job is to pick your words apart and use them against the person you’re trying to help.

Give your statement only to one of these three parties:

- The victim’s attorney (the best option).

- The victim directly.

- The police, if they request it for their investigation.

That’s the entire list. Protect your words. Ensure they are used as a shield for the innocent, not a weapon for the insurer.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reading this post does not create an attorney-client relationship. Every case is different, and you should consult with a qualified attorney for advice regarding your individual situation.

If you saw something, and someone needs your help, you’re in the right place. Call Conduit Law. We’ll talk it through—no charge, no pressure, no nonsense. I got you.

Written by

Conduit Law

Personal injury attorney at Conduit Law, dedicated to helping Colorado accident victims get the compensation they deserve.

Learn more about our team